Jul 3, 2023

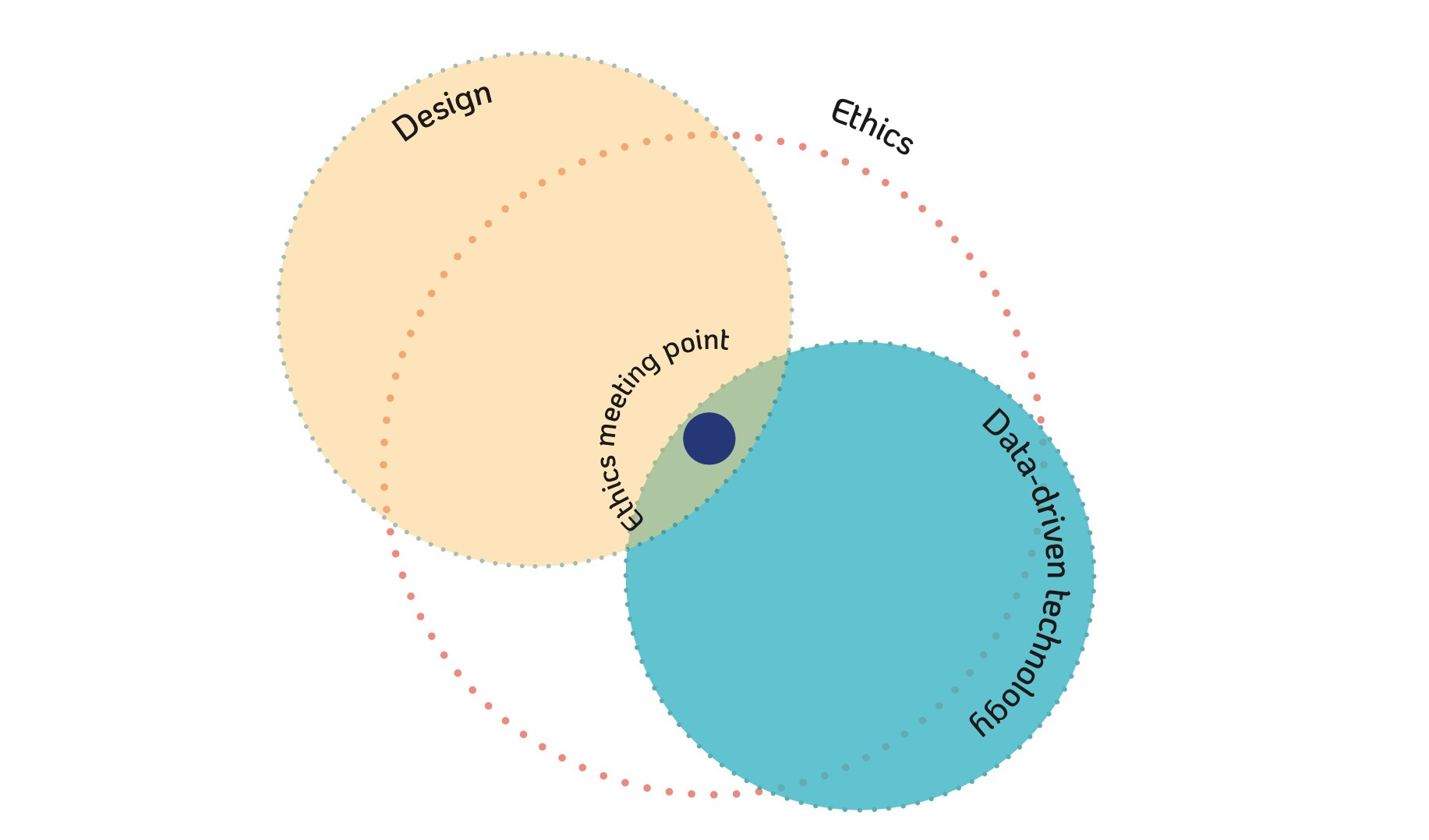

Why do we seek the overlapping point between Ethics, Design, and Data-Driven Technology for a service? How can we acquire sufficient knowledge about ethics and ethical design in today's context?

"What do you mean 'ethics' and 'ethical design'?"

Before we delve into the concept of ethical design, it is crucial to first understand what ethics itself means. Some individuals perceive ethics as being connected to morality, while others view them as having a political dimension, and still others consider them to be primarily based on philosophical or religious principles.

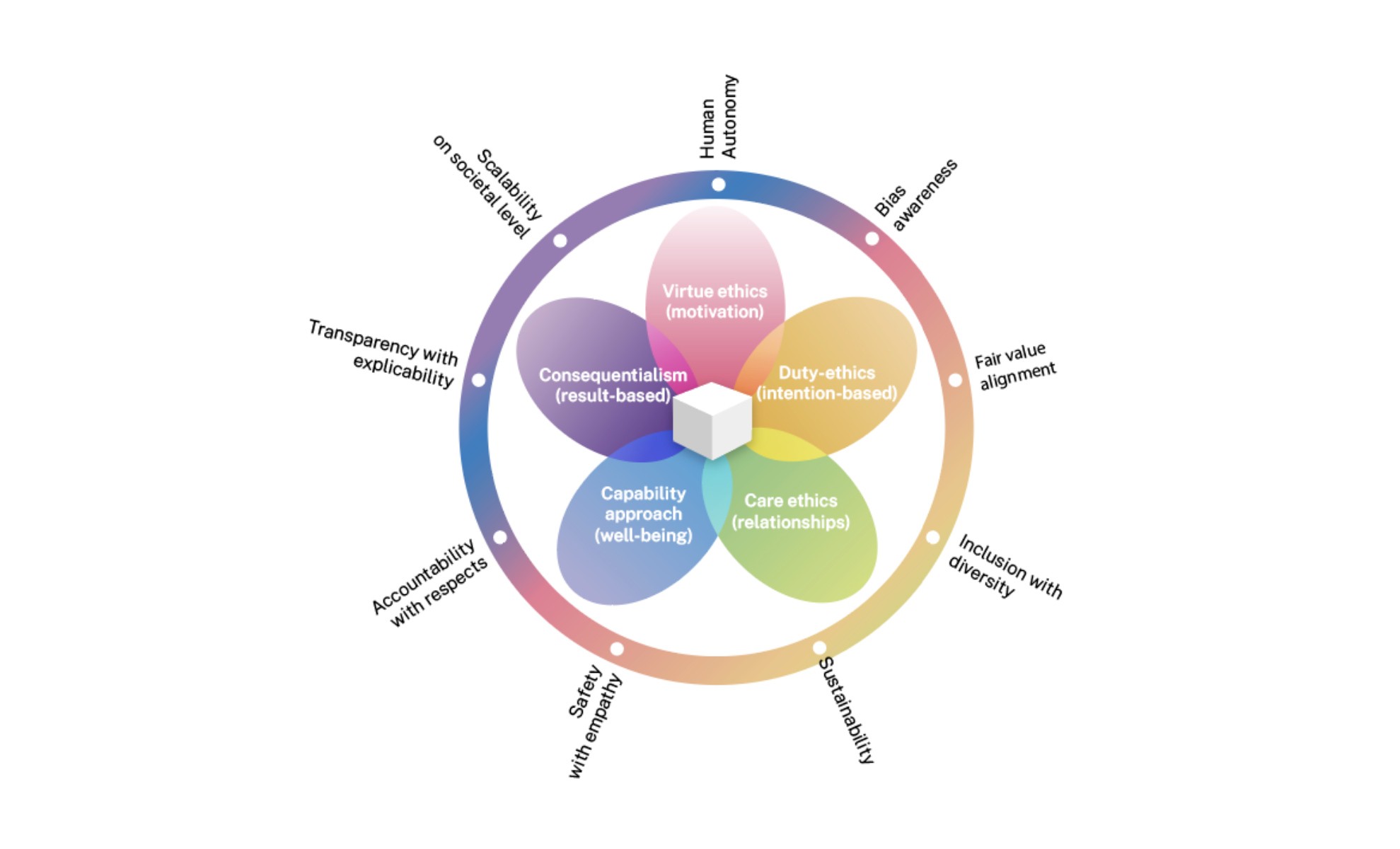

<the spectrum of ethics for design and technology>

The Unpack Ethical Design toolkit has been developed using a framework that incorporates five ethical notions known as 'the spectrum of ethics for design and technology.' This framework serves as a foundation for branching out into more specific and narrower ethical notions and values.

This article provides a summary of theoretical ethics and explores the relationship between design, technology, and ethics. It aims to provide further insight into the details of the framework's construction and its underlying rationale.

Ethics has diverse lenses through which today’s ‘goodness’ can be understood, as they have been developed and interpreted in various notions. Traditional dominant ethical theories such as virtue ethics, deontology ethics, and utilitarianism have been developed into more diverse forms of normative ethical theories such as the capability approach, justice ethics and care ethics. On a global scale, these complex and broad notions of ethics have been interwoven into morality, lifestyle as well as cultures, sometimes invisibly.

According to the Cambridge English Dictionary, the definition of ethic is, “a system of accepted beliefs that control behaviour, especially such a system based on morals.”, and the plural form, ethics, is “the study of what is morally right and wrong, or a set of beliefs about what is morally right and wrong.” (Cambridge University Press, n.d.,b).

Another definition is that, a singular ethic is “a set of moral principles: a theory of the system of moral values”, and the plural forms of ethics is “the principles of conduct governing an individual or a group” and “a set of moral issues or aspects such as rightness”. In addition to that, interestingly it is suggested that ethics are more specifically distinguished from morals. An individual’s morals usually describe someone’s particular values concerning what is right and what is wrong in a subjective preference. On the other hand, ethics can broadly refer to moral principles for the aspects of societal or global fairness although still being responsible for the action is still questionable (Merriam-Webster, n.d.).

According to the definition from Markkula Center for Applied Ethics at Santa Clara University, the researchers and academics address that there are certain defined misunderstandings about what ethics is.When it comes to thinking about ethical decisions, ethics is NOT; the same as feelings, the same as religion, the same thing as following the law, the same as following culturally accepted norms, nor science. Indeed, feelings, religions, laws, cultures and science are significantly important to influence how to view ethical situations and actions. Although these aspects tend to direct a variety of decision makings and the following actions however, they are not ethics themselves for ethical decision making (Markkula Centre For Applied Ethics, 2021).

In order to more specifically identify the ethical lenses we need, looking deep- er into theoretical and normative ethics which are born from different histories and moments in time would play an important role to help us to understand how ethics dwells in technology, design, and in us as humans unnoticeably. First, there are dominant traditional ethics which are globally well known: virtue ethics, duty(rule)-based ethics from deontology and consequentialist ethics from utilitarianism, which comes from both western and eastern philosophies.

Virtue ethics is the oldest philosophical ethical theory that started being defined by western philosophers, Plato and Aristotle, as well as being tracked to Mencius and Confucius in the East. (Hursthouse & Pettigrove, 2022). As seen in the meaning of the term ‘virtues’ rooted in the Latin ‘virtus’, the term is originally linked to the ancient Greek term ‘arête’which means ‘excellence’ in the broader concept ‘excellence of character’ with moral sense. In addition to that, the excellent character is understood by stable dispositions such as honesty, courage, moderation, and patience that promote their prossesor’s reliable performance of right or excellent actions. The concept of being ‘virtuous’ is hardly isolated within the western view, and was also established in East and South Asia, especially in Confucian and Buddhist ethics(Vallor, 2016).

“What kind of person would I want to become if I act like this?”

-based on virtue ethics

Virtuous action must be aligned with our feelings, beliefs, desires and perceptions, and is implemented by not only repeatedly performing courageous acts but also by cultivating virtues in ourselves. Furthermore, in order to become a virtuous person, moral reasoning and practical wisdom; guided by appropriate feeling and intelligence rather than mindless habits or fixed moral scripts, are fundamental to reflect the moral sense and actions in them, as in the virtue ethics, there is no fixed moral rule nor response in practice to both moral success and moral failure (Vallor, 2016).

The potential opportunity in virtue ethics can be developed through thoughtful reflection, and the potential ideals to be excellent as humans could be cultivated by a learning practice(Velasquz, et al., 1988).

“Everyone is obligated to act only in ways that respect the human dignity and moral rights of all persons based on the rules and their duty.”

-based on the duty-based ethics(Deontological ethics)

These two other dominant ethics are called ‘duty(rule)-based ethics’ (also known as ‘deontological ethics’) such as Immanuel Kant’s ‘categorical imperative’, and ‘consequentialist ethics’ (also known as ‘utilitarianism’), which are interestingly opposite claims to each other.

Deontology, the word that describes duty-based ethics, was derived from the term ‘deon’ meaning duty, and science (or study) of (‘logos’) in Greek. It concerns what people would do based on their duties without thinking about the consequences of their actions. The representative philosopher in deontological theory is surely Immanuel Kant who insisted on the moral quality of acts and a universal law for humanity which was focused on rational agents with their duties (Alexander & Michael, 2021).

As there are certain do’s and don’ts in duty-based ethics, in comparison to consequentialism, deontologists argued that there must be certain fixed rules to morality that teach people that some acts are ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ and that people have the duty to act accordingly. Although there are some criticisms in regards to living in universal moral rules that could potentially be oppressive towards the allowed people’s actions, there are clear, good points that the modern era can consider. Firstly, emphasising the value of every human being - equal respect provided with human rights. Secondly, clarifying which acts are wrong under the principles and rules and by doing so, providing certainty that reduces the ambiguity about ethics in practical situations and reality. Last but not least, it deals with intentions and motives with good wills which seems to fit with recent ordinary thinking about ethical issues nowadays (BBC, 2014d).

“Everyone must do whatever actions that will achieve the greatest good for the greatest number as a consequence.”

- based on the consequentialist ethics

In contrast, consequentialism only focuses on ‘good results’ and maximises happiness that can be measured. Consequentialists believe the act that brought the results is ‘right’. This is also called ‘utilitarianism’, which was proposed by empiricists, Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart. The general notion of consequentialism is that what is best or right is whatever produces good and makes the world better in the future, therefore the good consequences could maximise the utility for the largest number of people (Sinnott-Armstrong, 2019).

Thus, consequentialists believe that increasing the happiness of a whole society with intellectual and emotional fulfilment is the result they would aim for. There are several branches of consequentialism, one of them is ‘rule consequentialism’ which bases moral rules on consequences, which sounds practical and efficient. However, it is less flexible and impossible to predict all sets of consequences for decision-making. Another branch is ‘negative consequentialism’, which is the inverse of ordinary consequentialism. What it says is, ‘good actions are the ones that produce the least harm’. However, it also has critical flaws as it excludes minority groups who do not have the power to raise their voices. Also, it is easy to bias in favour of particular groups, which brings unfairness and inconsistent human rights by measuring and comparing the ‘goodness’ of consequences (BBC, 2014a).

Amartya Sen, who was an economist and a philosopher, initially developed the ‘capability approach’, which is a relatively new theoretical framework from non-western philosophy and has arisen from globalisation.

The capability approach entails two normative claims. First, it is centred on the individual’s freedom to achieve well-being and is rooted in the belief that it is of primary moral importance for human dignity. Second, the terms of well-being should be understood in terms of people’s ‘capabilities’ and ‘functionings’ understood as ‘opportunity freedom’ (capabilities) and ‘doings and beings’ (functionings). Due to its potential application in the real world, it has been employed in other ranges of normative theories such as development ethics, political philosophy, public health ethics, environmental ethics and climate justice as well as in education (Robeyns & Byskov, 2020). After Sen initiated the notion of ‘capabilities and functionings’, Nussbaum developed the ethical theory further so that it offers a viable approach to global ethics by providing a universal measure of human flourishing whilst respecting religious and cultural differences.

This approach could provide a meaningful guideline for the true flourishing of humanity along with the planet which the dominant ethical notions might overlook. For example, addressing sustainability for environmental protection relates to human flourishing, as well as human diversity with minority groups such as disabled groups from the global perspective could be more relevant to the ethical view in this globalisation (Kleist, n.d.).

The last normative ethical theory to look at is ‘care ethics’.

Care ethics is a relatively new conceptualisation that embraces interpersonal relationships on a global level which might cover some critical gaps from the dominant traditional ethics and the capability approach as they only focus on individuality and independence. Especially in practices of care, the relationships must be cultivated, needs must be responded to, and sensitivity must be demonstrated, as the values are defined to have trust solidarity, mutual concern and empathetic responsiveness. Following that, it offers suggestions for the radical transformation of society that include equal gender consideration in the social structure for social justice. As seen from the essence, the ethics of care has roots in the feminist ethics approach that appreciates the emotions and relational capabilities that enable morally concerned persons in actual interpersonal contexts to understand the best with respect. The interesting difference between care ethics and traditional ethics is that seeing ethics as ‘knowledge’ from the dominant ethics before, then care ethics claims ‘moral understanding’ involving attention, contextual, and narrative appreciation, and communication in the event of moral deliberation (Held V., 2006, pp.9-16).

In addition to that, the majority of care ethicists insist that care must be defined as practices (activities) and values that could do everything to maintain, contain, and repair our ‘world’ as a form of labour. This also brings some criticisms about its slavery morality, theoretically indistinct, sexually stereotyping of ‘Women’, and ambiguity.

There are still plenty more other ethical theories that direct their own ethical visions. However, even these five theoretical ethics have clearly shown diverse ethical views to see and understand what would be the ethical world we like to thrive in. Thus, each ethics showed that standing the theory alone would not be enough to define what would be ‘good’ and ‘right’. The attempt of understanding and seeing this unpredictable world through the multiple but essential ethical lenses could be the next step we can take on.

Then, what is the relation between ethics and design? Why should design relate to ethics?

‘Design’ has a variety of meanings that might show the connection to ethics. In terms of the literal meaning of ‘Design’ (noun and verbs); is to make (capability) or draw something (any forms) with intention (a particular purpose) with results(tangible or intangible) also it explains how it is made as the process (Cambridge University Press, n.d.a).

“Designing is fundamental to being human - we design, deliberate, plan and scheme in ways which prefigure our actions and makings - we design our world, while our world acts back on us and designs us.”

-Anne-Marie Willis, professor and editor of Design Philosophy Papers

Understanding the meaning of design from ontological designing perspective, designing can be radically understood as practices which are far more pervasive and profound than generally recognised by the actors. Throughout design, we understand how we ‘are’ as subjective beings, and how we can shape the ‘our world’ that acts back on us by ‘design’ in a reflective action (Fry’s formulation). This means including the ‘design of design processes’ whereby outcomes are prefigured and where-in the activation of particular design processes, as well as the ‘design effects’ that designers design (objects, spaces, systems, infrastructures) as the result (Willis, 2006, pp. 80 - 93).

The ethics of design have been also a matter of concern since the nineteenth century. The main claim is that design can create a product and a system based on humility that creates values for humans and their surroundings, a ‘nature’ that might be built upon ethics. The main ethical concerns in design include sustainability, ecologically sound or green design, and fair trading. The attempt of Attfield’s utility approach which is ‘fair shares for all’ highlighted opportunities to discuss the role of ethics in design at a more general level (Attfield, 1999, pp. 3-5).

At the early time of understanding traditional design was constructed in the Europe of the early twentieth century which was the heart of industrial production at the time. During this period of industrial technology, the idea that design requires active expertise and knowledge was established. However, since then the initial understanding has gradually been redefined to embrace new results (from product to service, and to organisations), new actors (from experts to users), and it changes its relationships with time (from closed-ended to open-ended processes). So design has now become a culture and a practice concerning how things should be in order to achieve desired functions and meanings (Manzini, 2015, p. 53).

Design is seen as a practical service to human beings in the accomplishment of individual and collective purposes. The end purpose is to help other people accomplish their own purposes. This is where the virtues as well as the responsibility of designers inevitably placed in a larger social, political, religious and philosophical context. Ethical guidance comes from personal morality, but also, several surroundings not only, professional organisations, the institutions of government, religious teachings, and philosophy.

Therefore, in the new modern days, design with ethics shows concerns about the individual’s moral behaviour and responsible choices in the practice of design. Ethical considerations have played a significant role in design thinking due to the development of scientific knowledge and the emergence of technology with design. The designers incorporate new knowledge about the world with technology and then, be more aware of the consequences for individuals, societies, cultures, and the natural environment (Buchanan, 2022).

“How does ethics play in this technology era?”

In this digital era, when we think about ethics, we do not recall only the classical definitions of ethics. This is because our life is rapidly changing with our surrounding technology, and the digitalistion evolves the notions of ethics in our real life.

Then we need to look into the relationship between ethics and technology in this technology-driven era.

Juan Enriquez urged that due to the rapid change of society with technology, people act reasonably to today’s prevailing norms , and are harshly judged in retrospect. Technology is the biggest player in this change as it provides alternatives that have never been shown with firm ethical aspects before, and can fundamentally alter our notion of what is right and wrong. Furthermore, our absolute beliefs are evolving often into the opposite of what we once accepted and believed in our past, as ethical norms are shaped accordingly (Enriquez, 2020, pp. 5 - 8).

There are more and more increasing questions towards technology ethics, such as whether new forms of technologies provide us with the ‘power’ to act, which means that we have to make more ‘right’ choices than ever. However, it makes human beings more vulnerable and interdependent as individuals, either flourishing or collapsing together.

Technologies are experimenting with human life on a global level, as there is no border for technology saying the purpose that contributes to a better sense of the world is to make better sense of choices. However, cutting-edge technologies with data-driven tools/models such as AI and ML have fundamentally ethical aspects to consider. This tricks us into making mistakes when it comes to trading-off morality for efficiency. Efficiency from technology can be a significant benefit to humanity, but it doesn’t mean that it is based on morality (Green, 2017).

Therefore, technology and Ethics are interconnected. Because technology is the key player that shapes the social, political, economic, biological, psychological and environmental conditions in which humans strive to flourish as the medium. Moreover, technological design and implementation decisions are in the hands of few ‘innovators’ who do not embody the interests/needs/values of all. They often focus on manifesting an impersonal drive to efficiency, optimisation, measurement, control and other machine values at the expense of humane values such as justice, compassion, nobility, freedom and leadership that affect future generation’s ethical norms. The demand is growing to understand that the power of technology also must match the growth of human wisdom and responsibility of ethics to balance them (Vallor, et. al., 2018).

“As long as there is technological progress, technology ethics is not going to go away, in fact, questions surrounding technology and ethics will only grow in importance.”

-Brian Green, Director of Technology Ethics at the Markkula Center for Applied Ethics

What ethical aspects and principles in technology do we acknowledge?

According to ethicists and technology ethics institutes like ‘ICAEW’, ethics in technology fundamentally require strong frameworks for ‘accountability’ that provide vital support for ethics. This is because technology creates new tensions and pressures for ethics and accountability. In meaning, it must be a different accountability structure to the traditional form, as the new way in a new technology age needs to be shared effectively between a variety of domains such as technology specialists, business users and senior management, in order to avoid the gap and ensure clear hand-overs. Also, due to the new evolving the notions of ethics with technology, there are new difficult questions coming up in regards to understanding the genuine meaning of fairness, human dignity, social justice, and common goods in different levels of stakeholders and social structures, as well as the ability to identify unintended consequences and harms caused by technology (ICAEW, 2019).

Having a look through the relations of ethics in design and technology shows its complexity of interplay and the following impacts inter affecting people, society and technology that shape today and tomorrow. Unfortunately, there is yet no universal code of ethics that people and society rely on. However, there are growing demands about how we need to understand and act upon the relations between ethics, design and technology for global businesses and societies. We must ask ourselves.

"Are we keeping up our personal ethical principles along with this rapid change of technology development?"

“What are ethical problems coming up? What is the ethical problem in design with data-driven technology for a service?”

In the process of developing data-driven solutions like AI and ML, there are no standardised practices to note where all of the data has come from and how it was acquired. What biases or classificatory politics do these datasets contain that will influence all the system that relies on them? What is data? Basically, data in the twenty-first century became whatever could be captured. In this sense, it can be a resource to be consumed, a flow to be controlled, or an investment to be harnessed. The interesting thing is that the data collection is not only from data professionals, but also their institutions and the technologies the innovators deployed.

In addition, there are more and more data experts raising their voices regarding new values they believe ought to embed in the technology, rather than continuing to extend the outdated and existing unfairness in the world.

O’Neil, a well-known author, data scientist and mathematician, witnessed enormous paradoxes throughout her career in the use of algorithmic models in the big data economy. The models used as a digital service for many contain discrimination like racism, unfairness, inequality and injustice. The growing misuse of mathematical models that make use of big data for automated decision-making for our future service solutions lacks foresight, particularly when it comes to the harmful consequences. Despite global innovators always dreaming about future solutions, ironically, they collect, label, and classify the datasets from historical data in the past in order to train the machine, which could be blended with unfair biases and discrimination (O’Neil, 2016).

“Big Data processes codify the past. They do not invent the future. Doing that requires moral imagination, and that’s something only humans can provide. We have to explicitly embed better values into our algorithms, creating Big Data models that follow our ethical lead. Sometimes that will mean putting fairness ahead of profit.”

-O’Neil, 2016, Weapons of Math Destruction. 204p

This separates ethical questions away from the technical reflection with wider problems, where the responsibility is not easily recognised, or seen beyond the scope of research or deployment. The problem is not only one of biassed datasets or unfair algorithms and of unintended consequences. It is also reproducing ideas that damage vulnerable communities and reinforce current injustices without knowing (Crawford, 2021. pp. 115 -117).

Then, why should design think about this ethical crisis in technology?

Nowadays the significance of interplay between ethics, design and technology is becoming crucial. Due to the complexity of sociotechnical organisations mixed with different domains to work with, the design process is not only considered solely by the domain of design. Technology is a team sport, and the current modern tech is made by teams of engineers, designers, product managers, and data scientists, relying on multiple underlying layers (Bowles, 2020).

Design is a key action and plan of creating the services and outcomes with technology. As part of technology creators, designers try to play a significant role on user-centred service with empathy.

“Why do we continue to design technologies that reproduce existing systems of power inequality when it is so clear to so many that we urgently need to dismantle those systems?”

-Sasha Costanza-Chock, a communications scholar, designer, and activist

Sasha Costanza-Chock addressed the current dilemma in regards to design practices for technology enabled solutions. When it comes to designing technology, the practices create a missing gap to certain marginalised groups, even during most design processes it is impossible to see and consider. Because most design processes today are not structured intersectionality, this can cause inequitable distribution of benefits and burdens that are continually reproduced in the existing out-dated norms in the capitalist model. The lack of awareness of ‘intersectionality’ and the ‘matrix of domination’ in the design process cause harmful outcomes falling on the marginalised groups who are poorer with less power in society. (Costanza-Chock, 2020, pp. 17 - 39).

The interconnected powerful impacts from design and technology, the role of designers and the other actors are changing alongside the technology. Today’s designers who want to be part of creating technological outcomes need to be systems thinkers, experts in regulation, collaborators, communicators, and fearless enough to raise their voices when it comes to ethical practices. There is more to learn about how to be accountable for what we are doing, which is rarely taught by design education.

Thus, designers must become a gatekeeper for ethics. Over the last decade, the role of the designer has become astonishingly complex not only from the technology as it is ethically complex (Monteiro, 2019, pp. 18, 30).

I hope I haven't lost you yet. The main point I argue in this framework is that we need lenses to examine ethical values and envision them as a spectrum, rather than viewing them as black-and-white or simply as a matter of right and wrong for judgement.

As emerging technology brings new problems of collective responsibility for creators which are likely to impact future persons, groups, systems and stakeholders, and have unpredictable consequences that unfold on an open-time horizon (Vallor, 2016).

The five ethical theories might help us recognise and describe ethical issues that, along with other harms, have arisen from the heavy use of technological applications nowadays. This framework, which details and utilises five ethical lenses, is not an universal that can apply for all contexts and fields, but it is specifically focused on ethical principles and values within the context of design processes and data-driven technology.

Each ethics theory has a different view that draws what is ‘good’ and what is ‘wrong’ but there are also following drawbacks that lead to limitations. Therefore, relying on a single ethical theory is insufficient to see the practical ethics implication to be learnt. In the literature review, the five ethical theories; virtue ethics, duty-ethics, consequentialist ethics, the capability approach and care ethics, are explored in order to seek the interdisciplinary relationship between ethics, design and technology.

** This article contains a portion of the M.A. thesis research titled "Unpacking the Spectrum of Ethics - Opening a Safe Space and Time for Collaborative Ethical Disclosure" written by Jiye Kim, MA Integrated Design at Köln International School of Design (KISD).

The academic research was supervised by Prof. Birgit Mager (Service Design) and Prof. Dr. Lasse Scherffig (Integration Design) at KISD from March 2022 to January 2023.

About the author:

I am an ordinary person who is not perfect but has a lot of curiosity about "why we design and what we design for" in both theoretical and practical design ethics. I have been fortunate to have opportunities in education and various work experiences as a designer in South Korea and several European countries. The research I conducted was influenced by these previous experiences and focused on exploring the meaning of "ethical" design in creating technological services. These opportunities have allowed me to witness a spectrum of possibilities in ethical design practices, empowering designers to determine not only what we do but also how we do it.

Bibliography:

-Attfield J. (1999). Utility Reassessed - The role of ethics in the practice of design. pp. 3-5.

-Alexander, L. and Michael M. Deontological Ethics. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2021 Edition). Edward N. Zalta (ed.). https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2021/entries/ethics-deontological

-Alkire S.(n.d.) The Capability Approach and Human Development. Oxford Poverty & Human Development Initiative (OPHI), University of Oxford. Slide: pp. 6-16

-BBC. (2014a). Consequentialism. Ethics guide. https://www.bbc.co.uk/ethics/introduction/consequentialism_1.shtml

-BBC. (2014b). Duty-based ethics. Ethics guide. https://www.bbc.co.uk/ethics/introduction/duty_1.shtml

-Buchanan, R. (2022)Design Ethics. Encyclopaedia of Science, Technology, and Ethics. (Retrieved December 20, 2022). Encyclopedia.com. https://www.encyclopedia.com/science/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/design-ethics

-Cambridge University Press. (n.d.a). definition of design from the Cambridge Advanced Learner’s Dictionary & Thesaurus. Cambridge Dictionary. https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/design

-Crawford, K. (2021). Atlas of AI. 95 - 118.

-Costanza-Chock, S. (2020). Design Justice - Community-Led Practices. 17 - 54

-Enriquez, J. (2020). Right /Wrong. 5-8p

-Green, B. P.(2017). What is Technology Ethics?. The Markkula Center for Applied Ethics at Santa Clara University. https://www.scu.edu/ethics/focus-areas/technology-ethics/

-Held, V. (2006). The Ethics of Care: Personal, Political, and Global. 9-16

-Hursthouse, R. and Pettigrove, G.(1999). Virtue Ethics. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2022 Edition). Edward N. Zalta & Uri Nodelman (eds.). https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2022/entries/ethics-virtue.

-Markkula Center for Applied Ethics at Santa Clara University. (2021) the product of dialogue and debate about the framework for thinking ethically. https://www.scu.edu/ethics/ethics-resources/a-framework-for-ethical-decision-making/

-Merriam-Webster. (n.d.). Ethic. Merriam-Webster.com dictionary (Retrieved December 23, 2022.). https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/ethic

-O’Neil, C. (2016). Weapons of Math Destruction.

-Osmani, S. R. (2016) The Capability Approach and Human Development: Some Reflections, New York. UNDP Human Development Report THINK PIECE. United Nations Development Programme.

-Sinnott-Armstrong, W. (2019). Consequentialism. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2022 Edition), Edward N. Zalta & Uri Nodelman (eds.). https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2022/entries/consequentialism

-The Ethics Centre. (2016). Ethics Explainer: Consequentialism.(Article - Big Thinkers + Explainers. https://ethics.org.au/ethics-explainer-consequentialism/

-Vallor, S., Green, B., and Raicu, I. (2018a). Ethics in Tech Practice: An Overview. The Markkula Center for Applied Ethics at Santa Clara University. pp. 3 - 7.

-Vallor, S. (2016).Technology and the Virtues - A Philosophical Guide To a Future Worth Wanting. 17-34

-Vallor, S. Raicu, I. and Green, B. (2022). Technology and Engineering Practice: Ethical Lenses to Look Through. The Markkula Center for Applied Ethics at Santa Clara University.

-Velasquez, M., Andre, C., Shanks, T., S.J. and Meyer, M. J. (1988) Ethics and Virtue. Issues in Ethics V1 N3(Spring 1988 Edition).